From left: Mathew Ahmann, director of the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice; Cleveland Robinson, chairman of the Demonstration Committee; A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Rabbi Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress; Joseph Rauh Jr., attorney; John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; and Floyd McKissick, chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality.

Note: Click these icons to hear bits of audio from WGBH's original, 1963 coverage.

It was a warm, beautiful late summer day in Washington with a high that reached 82 degrees. Across the country -- and the world -- it was news about the thousands traveling to Washington that captured attention. Live coverage began early in the morning.

More than 30 special trains, carrying 26,000, and 880 buses, carrying 33,000, were expected to usher people into Washington. Early crowd estimates numbered 82,000. There was no sign of how large the gathering would be, and little did anyone know that the crowd would swell to 175,000 by the end of the day.

The Washington Police didn't know what would happen when the people got to the site of the March. Malcolm Davis, a reporter for the National Educational Radio Network, the precursor to National Public Radio, was situated on the Washington Monument grounds. Here's his report from early in the day:

The main area here is comparatively empty. It is slowly filling up, but nothing too much. Surrounding the area, there are all sorts of lunch counters, and comfort stations, and many trucks that are, I presume, here to service all of these people that are attending the march. Radio and television cameras are still checking out here, and we seem to be at this point, from all the radio and television people, the only people on the air at the time.

There was a great amount of apprehension about the march in the nation's capitol. Though the civil rights strategy was non-violent, there was worry that the protest would turn violent or attract people who wanted to stir up trouble. George Lincoln Rockwell, who was the leader the of Nazi Party in the Washington area, marched along the northeast side of the Washington Monument briefly as police stood by.

The Washington Police designed an extensive safety plan for the event. ERN reporter Mike Price read part of that plan.

This is the most important occasion that the Metropolitan Police Department has ever faced in its long and distinguished history.

It is imperative that every man and every official do his utmost to see that these orders are carried to the end that when the rally is over and the participants have disbursed to their various homes in the cities and states, they may look back on this day with pleasure. And that there will linger in their hearts a genuine esteem for our department.

A lot of people were angry about the protestors, and didn't understand what the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was about. These were tense racial tension times in the country. It was the mid-point of what we know now as the modern civil rights movement. Civil rights organizers had been engaged in nonviolent street protests all over the South, but their protests had been met with violence, and many participants suffering beatings and deaths.

But the crowd had been told to dress well -- as if they were going to church. The atmosphere was calm. And it remained peaceful, even as it became clear that crowd predictions were too low. Within a few short hours what was a walk of just a few minutes became a half hour march as the crowd swelled. By noon, the police estimated between 175,000 and 200,000 people gathered on the one-mile stretch between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial.

A. Phillip Randolph, a dean of the civil rights movement and the motivating force behind the March on Washington, along with other civil rights leaders, had pushed for this March, even though President John F. Kennedy tried to talk them out of it. Kennedy was worried the March would thwart his efforts to get political support for a civil rights bill that he had put forward.

Randolph, who was the founder and president of the Sleeping Car Porters, would not be deterred. He had been in charge of a civil rights march in 1941 that did not bring about results or change, so he was determined to make the March for Jobs and Freedom work. Randolph reminded the crowd that day about the power of protest:

![Photograph by Rowland Scherman/National Archives

Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. [A. Philip Randolph, organizer of the demonstration, veteran labor leader who helped to found the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, American Federation of Labor (AFL), and a former vice president of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO).]](img/randolph.png)

A. Phillip Randolph

The plain and simple fact is that until we went into the streets the federal government was indifferent to our demands. It was not until the streets and jails of Birmingham were filled that Congress began to think about civil rights legislation. It was not until thousands demonstrated in the South that lunch counters and other public accommodations were integrated.

It was not until the Freedom Riders were brutalized in Alabama that the 1946 Supreme Court decision banning discrimination in interstate travel was enforced, and it was not until construction sites were picketed in the North that Negro workers were hired.

Those who deplore our militants, who exhort patience in the name of a false peace, are in fact supporting segregation and exploitation. They would have social peace at the expense of social and racial justice.

Today, this historic march is known simply as the March on Washington, but it's official title was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Those last words meant something. At the time, unemployment was high, and black people earned significantly lower wages than whites. At some point during the day, the analogy was made that black maids were earning just $5 per week in households with income of $100,000. The word "freedom" was included in the title of the march because civil rights organizers wanted to pressure Congress to pass civil rights legislation that would abolish segregation, which was having a huge impact on the ability of black folks to improve their lives.

During the March, civil rights leaders spent their time articulating support for the bill as well as a series of demands. Here's the chief architect of the day's event -- Bayard Rustin -- articulating support for the bill as part of a series of demands.

Friends, at five o'clock today, the leaders whom you have heard will go to President Kennedy to carry the demands of this revolution. It is now time for you to act. I will read each demand and you will respond to it. So that when Mr. Wilkins and Dr. King and the other eight leaders go, they are carrying with them the demands which you have given your approval to. The first demand is that we have effective civil rights legislation, no compromise, no filibuster, and that it include public accommodations, decent housing, integrated education, FEPC, and the right to vote. What do you say?

Number two, number two: They want that we demand the withholding of federal funds from all programs in which discrimination exists. What do you say?

We demand that segregation be ended in every school district in the year 1963.

We demand the enforcement of the 14th Amendment, the reducing of congressional representation of states where citizens are disenfranchised.

We demand an executive order banning discrimination in all housing supported by federal funds.

We demand that every person in this nation, black or white, be given training and work with dignity to defeat unemployment and automation.

We demand that there be an increase in the national minimum wage so that men may live in dignity.

We finally demand that all of the rights that are given to any citizen be given to black men and men of every minority group including a strong FEPC.

The FEPC Rustin refers to was the Fair Employment Practices Commission, which would eliminate discrimination in hiring. Kennedy had refused to include it in his civil rights bill, fearful that it would doom the bill. The bill did end up passing with the FEPC provision well after Kennedy's death in November of 1963.

The March on Washington was a protest for better jobs and fair wages, but protestors also wanted the nation to hear from people who suffered daily discrimination in all areas of their lives.

Here's Percy Lee Atkins, the head of the NAACP in Mississippi interviewed by an ERN reporter:

Reporter: Mr. Atkins, why have you come to Washington?

Atkins: I came because we want our freedoms and we want our jobs and other things. What it's going to take to have our freedom.

Reporter: What specifically do you mean when you say you want freedom?

Atkins: Well, we want the opportunity to have the same things the white people have. Also, we would like to have the same schools, that they would have just as good as theirs, and we would like to have good jobs just the same as they do, and we want the same salary.

Joining the thousands of black people traveling by bus, train and automobile were supporters of all races, labor organizers, and the clergy. For the clergy, civil rights issues were a moral quest. Most people think of the more dramatic civil rights problems being in the South, but there would be plenty of controversy surrounding civil rights in the Northeast. Here's an exchange with some Massachusetts ministers:

Wooten: My name is Roger Wooten from Acton, Mass.

Lancier: Dean Lancier from Acton, Mass.

Reporter: And you're both clergymen?

Wooten: That's right.

Reporter: What made you come to Washington?

Wooten: Well, we're very much interested in supporting the civil rights movement, I think, Dean. Is that right?

Lancier: Yes, that's right. As I told our church this I believe in and, therefore, that's why I'm here.

Reporter: Now Acton is a pretty small town in Massachusetts. Do you have any civil rights problem there?

Lancier: It just started when we had a Negro family move in four houses up from us a month ago.

Reporter: Is that so, and how are they feeling?

Lancier: This is the second family in town. Not too well at first but they are being accepted now.

Reporter: Do you think the March will help them in some way?

Lancier: Indirectly and in the long run.

Though the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is perhaps best known for one speech -- what's now known as the "I Have a Dream" speech by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. -- there were several speeches of note at the all day event.

Roy Wilkins, the head of the NAACP at the time, was one of the main speakers that day. Wilkins was one of the 10 who sponsored the march. He detailed recent violent incidents:

Now, my friends all over this land, and especially in parts of the deep south, we are beaten, kicked, maltreated, shot, and killed by local and state law enforcement officers.

It is simply incomprehensible to us here today, and to millions of others far from this spot, that the United States government, which can regulate the contents of a pill, apparently is powerless to prevent the physical abuse of citizens within its own borders.

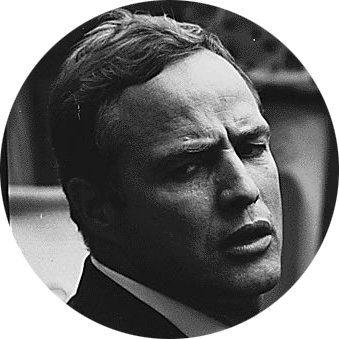

Reporters caught up with some celebrities who lent their support by being there. Here's actor Marlon Brando, who said he came to the March that day to give his full support to civil rights legislation pending before Congress.

Marlon Brando

Reporter: What are your impressions of the demonstration thus far today?

Brando: I think they have been impressive. I think that the number of people here -- of course -- this is an historical, unprecedented occasion. At no time in the history of America have this number of people assembled in Washington with a single cause such as civil rights.

Reporter: Do you foresee any future activities on your part of one or another sort in support of this movement for civil rights?

Brando: There was some discussion today on the bus for the first time about actors trying to get their films prevented from being shown in segregated theaters. And I think that that is a very clear answer to those detractors and the people who have taken our interest lightly and who feel that this is just a publicity cause. We don't stand to gain any money by that. We stand to lose something. But I think that the negroes have lost for 150 years, and I think that we should share their sense of loss and their sense of gain.

Labor was very much out front for the march. Labor leader Walther Reuther, who was the head of AFL-CIO, joined the fellow march sponsors on stage with a call to white people:

I am here today with you because with you I share the view that the struggle for civil rights, and the struggle for equal opportunity, is not the struggle of Negro Americans, but the struggle for every American to join in.

For 100 years, the Negro people searched for first-class citizenship. I believe that they cannot and should not wait until some distant tomorrow. They should command freedom now, here and now. It is the responsibility of every American to share the impatience of the Negro Americans.

American democracy has been too long on pious platitudes, and too short on practical performances in this important area.

Now one of those problems is what I call, that there are too much high octane, hypocrisy Americans. There is a lot of local talk about brotherhood, and then some Americans drop the brother and keep the hood.

International superstar Josephine Baker flew to Washington from France for the March. She had moved out of the country because she was unable to make a living in the United States as a black actress. In fact, she was one of several black American actors who moved to France as a refuge from the segregation in America, so for her to come back for this particular event was a big deal.

Josephine Baker

I want you to know that this is the happiest day of my entire life. I'm glad to see this day come to pass.

This day, because you are on the eve of complete victory, and tomorrow, time will do the rest. I want you to know also how proud I am to be here today, and after so many long years of struggle fighting here and elsewhere for your rights, our rights, the rights of humanity, the rights of man, I'm glad that you have accepted me to come. I didn't ask you. I didn't have to. I just came because it was my duty and I'm going to say again you are on the eve of complete victory.

The crowd also heard from civil rights stars like Birmingham's Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth. Shuttlesworth was revered by this crowd, who knew of his story of having walked away unscathed when his house was bombed. He stoked the crowd's emotions:

Fred Shuttlesworth

We're going to march.

We're going to walk together. We're going to stand together.

We're going to sing together. We're going to stay together. We're going to moan together.

We're going to groan together and after a while, we will have freedom, freedom, and freedom now.

And then there was veteran organizer Daisy Bates, who prepared nine black students at Little Rock's Central High to face a segregationist mob. She was one of several women in the movement, including Diane Nash and Rosa Parks, who was honored for their service that day. Here you get a sense of Bates' determination:

Daisy Bates

Mr. Randolph, friends, the women of this country [inaudible] our pledge to you, to Martin Luther King, Roy Wilkins and all of you fighting for civil liberties -- that we will join hands with you as women of this country.

Rosa Gregg, Vice President; Dorothy Height, the National Council of Negro Women; and the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority; the Methodist Church Women, all the women pledge that we will join hands with you.

We will kneel-in. We will sit-in until we can eat in any corner in the United States. We will walk until we are free, until we can walk to any school and take our children to any school in the United States. And we will sit-in and we will kneel-in and we will lie-in if necessary until every Negro in America can vote. This we pledge to the women of America.

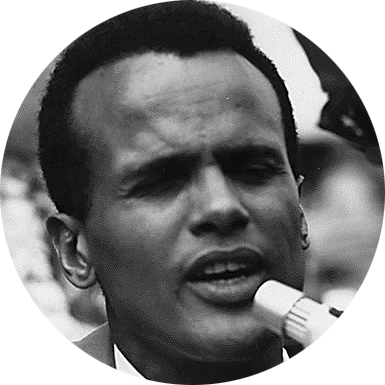

Singer and activist Harry Belafonte, who is still active in civil rights today, represented 1,500 artists supporting the demonstration. Those 1,500 artists included Charlton Heston, Paul Newman, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis Jr., Lena Horne, Gregory Peck, Rita Moreno, Burt Lancaster, Ossie Davis, and Rube Dee. Here's Belafonte:

Harry Belafonte

We also know that freedom is not license. Everyone in a democracy ought to be free to vote. But no one has the license to oppress or demoralize another.

We also know, or we would not be here, that the American Negro has endured for many generations in this country, which he helped to build, the most intolerable injustices. To be a Negro in this country means several unpleasant things. In the deep South, it often means that he is prevented from exercising his right to vote by all manner of intimidation up to and including death. This fact of intimidation is a great weight in the life of any Negro and though it varies in degree, it never varies in intent, which is simply to limit, to demoralize, and to keep in subservient status more than 20 million Negro people.

As the reporters on the scene noted, despite initial concern about the program everything seemed to be running smoothly. But behind the scenes, there was a brewing controversy.

The night before the March, some of the top organizers got a look at John Lewis' prepared remarks. Lewis, 23, was the newly elected national chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. That group represented the young civil rights workers who often expressed impatience with their older cohorts. Lewis' words, tone, and delivery showed some of that edge that the veterans were uncomfortable with.

We march today for jobs and freedom, but we have nothing to be proud of, for hundreds and thousands of our brothers are not here -- for they are receiving starvation wages or no wages at all. While we stand here, there are sharecroppers in the Delta of Mississippi who are out in the field working for less than $3 a day, 12 hours a day.

Lewis agreed to tone down his remarks at the personal request of A. Philip Randolph. But Randolph also defended Lewis' right to keep some of his strong statements.

During the first part of the program, there's a picture that captures the moment Lewis, Courtland Milloy and Bayard Rustin huddled behind the Lincoln Memorial, rewriting and cutting the original speech.

In his prepared remarks, Lewis wrote, "In good conscience we cannot support the administration's civil rights bill, for it is too little, too late."

Here's how he adapted those remarks:

We come here today with a great sense of misgiving. It is true that we support the administration's civil rights bill; we support with great reservation, however.

Do you know that in Albany, Ga., nine of our leaders have been indicted, not by the Dixiecrats but by the federal government for a peaceful protest? But what did the federal government do when Albany's deputy sheriff beat attorney C.B. King and left him half dead?

What did the federal government do when local police officials kicked and assaulted the pregnant wife of Slater King, and she lost her baby? Those who have said, 'Be patient and wait,' we must say that we cannot be patient. We do not want our freedom gradually, but we want to be free now. We are tired. We are tired of being beaten by policemen, we are tired of seeing our people locked up in jail over and over again, and then you holler, 'Be patient.' How long can we be patient?

We want our freedom and we want it now!

The end of Lewis' speech was particularly problematic for the older leaders who thought it volatile. Lewis planned to say: "We will march through the South through Dixie the way Sherman did. We will pursue our own ‘scorched earth,' and burn Jim Crow to the ground -- nonviolently. We shall fragment the South into a thousand pieces and put them back together in the image of democracy. We will make the action of the past few months look petty. And I say to you, wake up, America!"

But at the podium, the conclusion of his speech was tempered:

We will march through the South, through the streets of Jackson, through the streets of Danville, through the streets of Cambridge, through the streets of Birmingham.

But we will march with the spirit of love, and with the spirit of dignity that we have shown here today. By the forces of our demands, our determination and our numbers we shall shatter the segregated South into a thousand pieces and put them together in the image of God and democracy. We must say, 'Wake up America, wake up,' for we cannot stop and we will not and cannot be patient.

The final speech of the program was that of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. By this time, the march participants had been sitting or standing before the Lincoln Memorial for hours under the hot sun. Some cooled their feet in the reflecting pool. There were people as far as the eye could see.

An ERN reporter described the crowd that day as chanting "pass the bill." They held signs that read, "We demand an end to bias now!" They stretched as far as the eye can see -- they climbed the trees around the Lincoln Memorial. The crowd had heard singing, and speeches full of passion and drama, but King was the one they wanted to hear.

There are a couple of things to note as you listen to King's speech: At nearly 17 minutes, the speech ended up being the longest of the day. King described his speech as a new Gettysburg address -- designed to address the power brokers, and inspire the people.

His official speech ended right before he began the "I have a dream," section -- all of that was off-script and unplanned. King said afterwards that he sensed the crowd, and was led by a feeling. Though some have said Mahalia Jackson yelled to him "Tell them about the dream, Martin!"

King said he reached for those words realizing the people need something more, and he wanted to give hope to the thousands who had come.

As King went on beyond the prepared text, behind the scenes the production crew was upset because King was running long. They had no idea -- in the moment -- that King was delivering one of the greatest speeches of the 20th century.

President Kennedy was watching the speech on a black-and-white TV in the White House living quarters. He said of King's talent, "He's damn good, isn't he?"

Fifty years ago, if you were in Boston, you heard King's speech on WGBH Radio:

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have A Dream" Speech

Largely because of King's speech -- and the huge turnout -- the March on Washington was a high point of the civil rights movement. But less than a month after the March on Washington, four little girls attending Sunday school in Birmingham were killed in a church bombing. The reality was it would take more years, more legislation, and more violence before segregation was abolished and sweeping social change happened.

On August 28, 1963, nearing the end of 15 hours of live programming, ERN's Al Husan wrapped up the coverage:

The some 175,000 Americans are now beginning to leave the Lincoln Memorial.

Placards are once again being held up. On the podium now, directions are being given the demonstrators, as they've been called officially, as they return to their buses, and from buses to trains and to homes all over the country.

For a little bit of poetic symbolism here, a cloud has just darkened this area in front of the Lincoln Memorial, but the Reflecting Pool is in the sunlight.

The Washington Memorial, Congress is brilliantly silhouetted against the sky and flags are waving.